Cape Cod and the sea are forever linked. With fishing and whaling significant industries, the sea historically provided the livelihood for Cape residents. Beyond that, however, the sea offered up another source of local wealth — ship salvage. Before the construction of the Cape Cod Canal in 1914, ships carrying cargo and people were forced to navigate the treacherous waters off the Cape Cod coast, putting into ports in northern New England and farther north. Because of shifting sandbars — primarily around Chatham and along the Outer Cape — the waters were dangerous and deadly. Shoals and bars along the back of the Cape peninsula snagged so many unfortunate vessels that 13 lifesaving stations were built to aid shipwrecked mariners.

Between 1850 and 1980, approximately 3500 shipwrecks claimed lives and cargo along the Cape and Islands coastlines, so much so that in the 19th century there were at least two shipwrecks per month during winter. Not suprisingly, waters surrounding the Cape became known as an “ocean graveyard.” Many of these wrecks were lost forever beneath the unceasing rhythms of sea and sand. But a shipwreck along the shore became a bounty to be scavenged by locals, and nothing was left to waste. The wrecks were picked over so thoroughly by locals that they no longer exist intact, but rather in pieces – perhaps as a door in a house or as boards forming an old barn. These wrecks became a rich source of timber and were subsequently incorporated into historic Cape Cod buildings, past and present.

The more than one thousand barns currently on Cape Cod sport timbers recovered from shipwrecks, and our barn is no exception. And therein lies a tale, as many of the timbers in our barn were salvaged from the HMS Somerset, a British warship, wrecked during the American Revolution.

The HMS Somerset was an English Royal Navy gunship built in Chatham, England in 1748. Participating in several historic battles in the Seven Years War and the American Revolution, she sank in November 1778 in the waters off Provincetown.

Only three times since, the wreckage has been exposed by storms – in 1886, 1973, and 2010. Even though what’s left of the vessel lies on the shores off Cape Cod, it is still the property of the United Kingdom if they can prove that the salvage was from the HMS Somerset.

The wreck of the HMS Somerset lies buried beneath the sands about one mile west of the Peaked Hill Life Saving Station, and her history is intimately connected with Provincetown and the American Revolution.

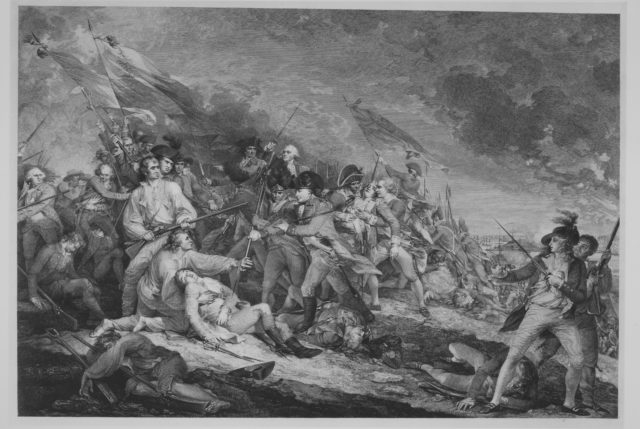

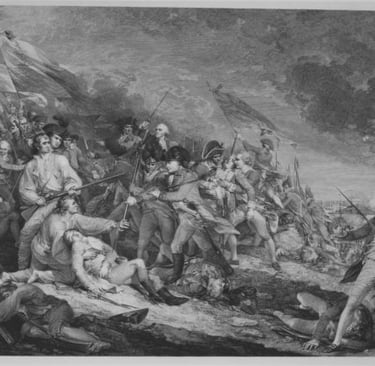

Records show she was a third rate frigate, carrying sixty-four guns, built in England’s Chatham dockyards and launched July 18th, 1748. In 1774 she left England for the North American Station, returned to London in 1776, and sailed to North America again in 1777 to take an active part in the war of the Revolution. The Somerset was present at the bombardment of Charlestown, stationed as the third ship up the river in the line. Her job was to cover the landing of British troops when the battle of Bunker Hill was fought, and she was important enough for poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow to mention in one of his poems.

Her commander was the notorious Capt. Bellamy, known for taking every means to annoy the people of the defenseless coast. The Somerset often put into Provincetown harbor for supplies. Bellamy didn’t pay for supplies in money, instead allowing his chaplain to come ashore Sundays to preach to the populace. This was the payment for for eggs, butter and fish taken from the locals. Such was the local dread of seeing the frigate that mothers told their children the ship would carry them off, if they did not mind their parents; these threats had the desired effect on the children.

The people of Provincetown were unprotected during the Revolution, and the English held complete sway. Cape Codders had suffered greatly from the British blockade during the American Revolution, with commercial fishing and whaling virtually shut down. Some locals engaged in privateering and smuggling along the coast; others turned to the land for subsistence.

On November 2, 1778, Provincetowners saw the frigate returning, chased by a squadron of French men-of-war ships, she had been battling. The Somerset tried to make the port for safety, but the wind was blowing heavy from the north. Unable to weather Race Point, she struck the outer Peaked Hill Bar in a gale. The French vessels saw her there, fired a few shots, then sailed out to sea.

The beach was lined with locals who tried to save the lives of her crew, even though they were their enemies. The Somerset launched its boats, but they were dashed to pieces alongside with those in them drowned. Heavy guns, shot, and other articles were thrown overboard. The Somerset’s masts — broken off neat at the deck — were cut adrift. Finally, at high tide, the leaking ship was driven over the bar onto the shore by the force of wind and sea. Her surviving crew — more than 400 British sailors — were rescued by the people, to be held as prisoners of war. According to the official account of George Ourry, the ship’s captain at the time, only 21 men were lost during the wreck.

Captain Ourry was forced to walk under guard to Providence, Rhode Island , where he was exchanged for two American officers. Under the command of Captain Enoch Hallett of Yarmouth, the remaining prisoners were taken to Barnstable, and on to Boston. Except for one: the Somerset’s surgeon Dr. William Thayer, who was pardoned and stayed to give medical aid to the people of Provincetown and Truro.

Battle of Lexington and Concord

Before her ignoble end, the Somerset played a significant role in two historic Revolutionary events. In the first, things might have turned out differently the night of April 18, 1775 … if the duty watch of the frigate had been more alert.

That night Paul Revere had set out on his famous ride to Lexington to warn prominent Colonial leaders Samuel Adams and John Hancock that their lives were in danger. Departing Boston by rowboat to cross the Back Bay into Charlestown, Revere narrowly avoided notice by the Somerset, which was anchored there. Had he been stopped, the militias of many towns would not have arrived in Concord and the next day’s historic battle of Lexington and Concord might have had a different outcome. As it was, the ship’s gun crews kept rebel forces from following the retreating British troops to Charlestown on the evening of April 19.